Commodity Chain and Coffee Prices

Coffee is an extremely powerful commodity, reigning as one of the world’s most heavily traded product, and represents a very large food export and import of many countries. Coffee is, the fourth most valuable agricultural commodity, according to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization. The global commodity chain for coffee involves a string of producers, middlemen, exporters, importers, roasters, and retailers before reaching the consumer.

Coffee is a vital source of export for many of the developing countries that grow it. Some 20 million families in 50 countries now work directly in the cultivation of coffee; an estimated 11 million hectares of the world’s farmland are dedicated to coffee cultivation. Arabica and Robusta are the two principle species of coffee harvested today. Approximately 70% of the world’s production is the Arabica bean, used for higher-grade and specialty coffees, and 80% of this bean comes from Latin America. Robusta is grown primarily in Africa and Asia.

Most small farmers sell directly to middlemen exporters who are commonly referred to as coyotes. These coyotes are known to take advantage of small farmers, paying them below market price for their harvests and keeping a high percentage for themselves. In contrast, large coffee estate owners usually process and export their own harvests that are sold at the prices set by the New York Coffee Exchange. However, extremely low wages ($2-3/day) and poor working conditions for farmworkers characterize coffee plantation jobs.

Importers purchase green coffee from established exporters and large plantation owners in producing countries. Only those importers in the specialty coffee segment buy directly from the small farmer cooperatives. Importers provide a crucial service to roasters who do not have the capital resources to obtain quality green coffee from around the world. Importers bring in large container loads and hold inventory, selling gradually through numerous small orders. Since many roasters rely on this service, importers wield a great deal of influence over the types of green coffee that are sold in the respective markets.

Large roasters of North America usually have one blend of recipes and sell to large retailers – the Big Three (Kraft, which owns Maxwell House and Sanka, owned by Philip Morris; Procter & Gamble, which owns Folgers and Millstone; and Nestle) maintain over 60% of total green bean volume. Micro roasters, or those who roast up to 500 bags of coffee a year, offer the product we know as specialty coffee. Most roasters buy coffee from importers in small, frequent purchases. Roasters have the highest profit margin in the value chain, thus making them an important link in the commodity chain.

Retailers usually purchase packaged coffee from roasters, although an increasing number of retailers are also roasting their own beans for sale. The Specialty Coffee Association of America estimated that there are 10,000 cafes and 2,500 specialty stores selling coffee. Chains represent approximately 30% of all coffee retail stores. However, supermarkets and traditional retail chains are still the primary channel for both specialty coffee and non-specialty coffee, and they hold about 60% of market share of total coffee sales. Around the globe, the annual consumption of coffee is 12 billion pounds.

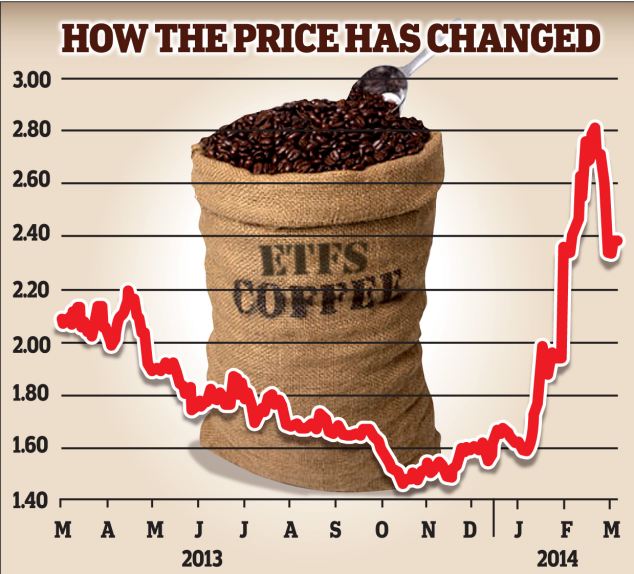

Coffee prices are set according to the New York “C” Contract market. The price of coffee fluctuates wildly in this speculative economy and tends to be very volatile. Most coffee is traded by speculators in New York, who trade approximately 8-10 times the amount of actual coffee produced each year. The single most influential factor in world coffee prices is the weather in Brazil. Droughts, rain and frosts are factors that accentuate the volatility, and that is how we experience the ups and downs of the market.

Specialty coffee is often imported at a negotiated price over the “C” market, which is considered a ‘quality premium’. Most of those premiums never reach the coffee farmer, but rather stay in the hands of the exporter. This creates a disincentive for farmers to increase their quality, as they do not receive the direct benefits of increased investment in producing better coffee.

Source: Wikipedia – The Free Encyclopedia